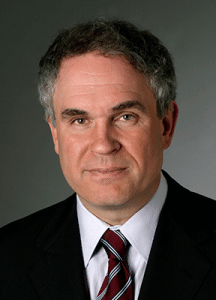

Glenn B. Pfeffer, MD, is director of the Foot and Ankle Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. He is also a co-director of the Hereditary Neuropathy Program and Co-Director of the Cedars-Sinai/USC Glorya Kaufman Dance Medicine Center. Dr. Pfeffer has written numerous scientific articles on orthopaedics and has edited seven academic textbooks on the foot and ankle. He has been treating foot and ankle problems in patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease for 25 years. He is a past president of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society and recently served as president of the California Orthopaedic Association. Dr. Pfeffer is frequently interviewed on foot and ankle topics and has been featured on CNN, Dancing with the Stars, Dateline NBC, Good Morning America, and in The New York Times.

Even though I don’t have CMT, I faced a problem similar to many of you – if and when to have foot surgery. I waited too long, and I don’t want you to make the same mistake. Ever since I can remember, I had pain and stiffness in my left foot and was unable to do certain things that came easily to my friends. My father, a professor of surgery in New York City, knew the best doctors for me to see. I saw countless specialists, but no one could ever come up with a diagnosis. There was nothing wrong and nothing to be done, they said. I came to accept my problem as normal, even though my symptoms worsened over the years. Ultimately, after I specialized in orthopaedic foot and ankle surgery, I made my own diagnosis. I had a tarsal coalition, a condition where some of the bones in the foot are joined together and do not move properly. It was not until 2004, the year that my term as president of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society came to an end, that I decided to have surgery. By then, however, the damage was already done. The foot joints that could have been saved when I was 17 were unsalvageable.

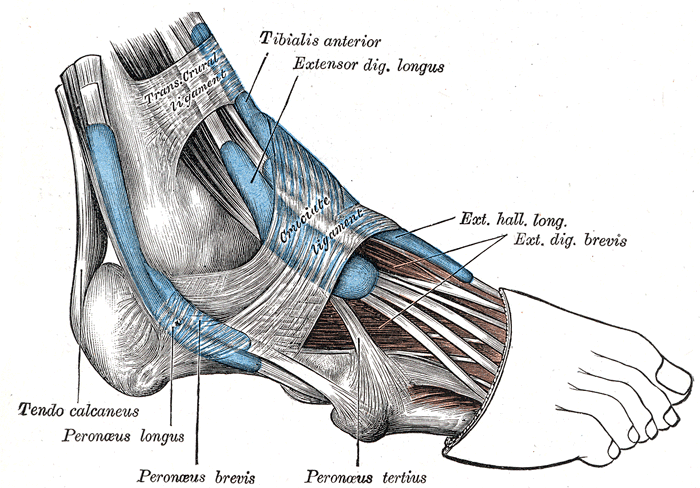

So, how do you know if you should have surgery? The key to making an informed decision is to understand what is happening to your foot. Your doctor may be able to help, although many are not familiar with CMT. The most common deformity in about 80 percent of patients with CMT is a cavovarus foot. The arch is high (cavus), the heel is turned inward (varus), and the toes are contracted (clawed). This abnormal foot shape results from years of imbalanced muscle-pull. The peroneus brevis muscle that stabilizes the ankle is often the first to weaken, followed by the tibialis anterior muscle that lifts up the ankle. The small intrinsic muscles that keep the toes straight also become weak. The result is a deformity caused by the over-pull of the muscles that remain strong (the posterior tibial, peroneus longus and extensor longus).

So, how do you know if you should have surgery? The key to making an informed decision is to understand what is happening to your foot. Your doctor may be able to help, although many are not familiar with CMT. The most common deformity in about 80 percent of patients with CMT is a cavovarus foot. The arch is high (cavus), the heel is turned inward (varus), and the toes are contracted (clawed). This abnormal foot shape results from years of imbalanced muscle-pull. The peroneus brevis muscle that stabilizes the ankle is often the first to weaken, followed by the tibialis anterior muscle that lifts up the ankle. The small intrinsic muscles that keep the toes straight also become weak. The result is a deformity caused by the over-pull of the muscles that remain strong (the posterior tibial, peroneus longus and extensor longus).

In mild cases, there may only be some slight imbalance and fatigue with walking. Often no treatment is needed, except for a physical therapy program directed at muscle strength (especially the peroneus brevis and tibials anterior muscles) and balance. A high-top shoe or a simple off-the-shelf brace may be sufficient.

As the muscles weaken and the deformity worsens, a bulkier and more complex brace is often needed. The goal of the brace is to stabilize the ankle and bring

As the muscles weaken and the deformity worsens, a bulkier and more complex brace is often needed. The goal of the brace is to stabilize the ankle and bring

the foot into a plantigrade position, where it is flat on the ground. If you are not comfortable in the brace, it is probably because these goals are not being met. Every week I see a patient in this situation, who has given up hope of walking with any normalcy. Their feet remain twisted inside of braces that are heavy and cumbersome. They are in pain, which is often attributed entirely to their neuropathy. But the diffuse calluses on the bottom and sides of the feet, caused by the abnormal stresses from the deformity, would be enough to cause anyone pain. All too often, no one has ever told them that surgery is an option. Look down on your foot in the brace. If your foot is not flat on the ground it is time to consult with an orthopaedic surgeon who specializes in the foot and ankle.

Surgery is not for everyone, however. The 20 percent of CMT patients who don’t have a cavovarus foot deformity will almost always do better with a brace. These are usually patients with complete paralysis below the knee (except for the Achilles which often retains some function). They never experience the muscle imbalance that creates a deformity. These patients all have a foot drop, and some surgeons still recommend an ankle fusion. I don’t suggest that approach. For these patients, a brace, specifically a ground-reaction-force brace (GRF), is by far the best option. While an ankle fusion is a great operation for someone who has a painful or deformed ankle from arthritis, without good muscle function in the rest of the foot, an ankle fusion does not do as well as a GRF brace. The GRF braces work by creating a spring action that comes from the stored energy within the brace as the patient bends the knee and flexes the brace. The brace stores energy with one step, and gives it back with the next, to create a remarkably fluid gait.

What are the goals of surgery for those with a cavovarus deformity? These feet are stiff, with little shock absorption. We don’t want to make them more rigid by fusing joints if we can avoid it. Instead, we want to preserve motion and get a foot that is flat on the ground with balanced muscle pull. Patients with CMT are generally otherwise healthy and tolerate surgery very well. We do these operations as an outpatient, with general anesthesia and a regional nerve block that provides post-operative pain relief for 24-72 hours. Typically, wedges of bone are removed from the heel and the big toe side of the foot to create a foot that is flat. The peroneus longus muscle is transferred into the weak peroneus brevis muscle to stabilize the ankle, and the posterior tibial muscle is brought from one side of the leg to the other to help lift up the ankle. Tight tissues are loosened, loose tissues are tightened, and the toes are straightened to fit into a shoe. It all sounds scary I suppose, but this is what orthopaedic surgery is all about. And the results are excellent.

What are the goals of surgery for those with a cavovarus deformity? These feet are stiff, with little shock absorption. We don’t want to make them more rigid by fusing joints if we can avoid it. Instead, we want to preserve motion and get a foot that is flat on the ground with balanced muscle pull. Patients with CMT are generally otherwise healthy and tolerate surgery very well. We do these operations as an outpatient, with general anesthesia and a regional nerve block that provides post-operative pain relief for 24-72 hours. Typically, wedges of bone are removed from the heel and the big toe side of the foot to create a foot that is flat. The peroneus longus muscle is transferred into the weak peroneus brevis muscle to stabilize the ankle, and the posterior tibial muscle is brought from one side of the leg to the other to help lift up the ankle. Tight tissues are loosened, loose tissues are tightened, and the toes are straightened to fit into a shoe. It all sounds scary I suppose, but this is what orthopaedic surgery is all about. And the results are excellent.

For the first two weeks after surgery it is important to rest up. The sutures come out after two weeks and a short leg non-weight bearing cast goes on for a month. After that, weight bearing is usually possible in a removable cast boot, and physical therapy begins. It can take up to a year to get used to your new foot, but it is worth it. The opposite foot can be operated on as soon as six weeks after the first. Outcomes are excellent, and even if the disease progresses, the foot is better off than it would have been without an operation. Many patients are able to get out of braces entirely, or at the very least decrease the size of their brace and walk with less pain.

It is important to remember that no one with CMT is born with a severe foot deformity. It develops over time. At some point, the reconstructive procedures discussed above become impossible. Chronic abnormal stress on the unbalanced cavovarus foot leads to ligament laxity, joint arthritis and fixed deformity. Joint fusions will then be the only option. That is what happened to me. Don’t let it happen to you.